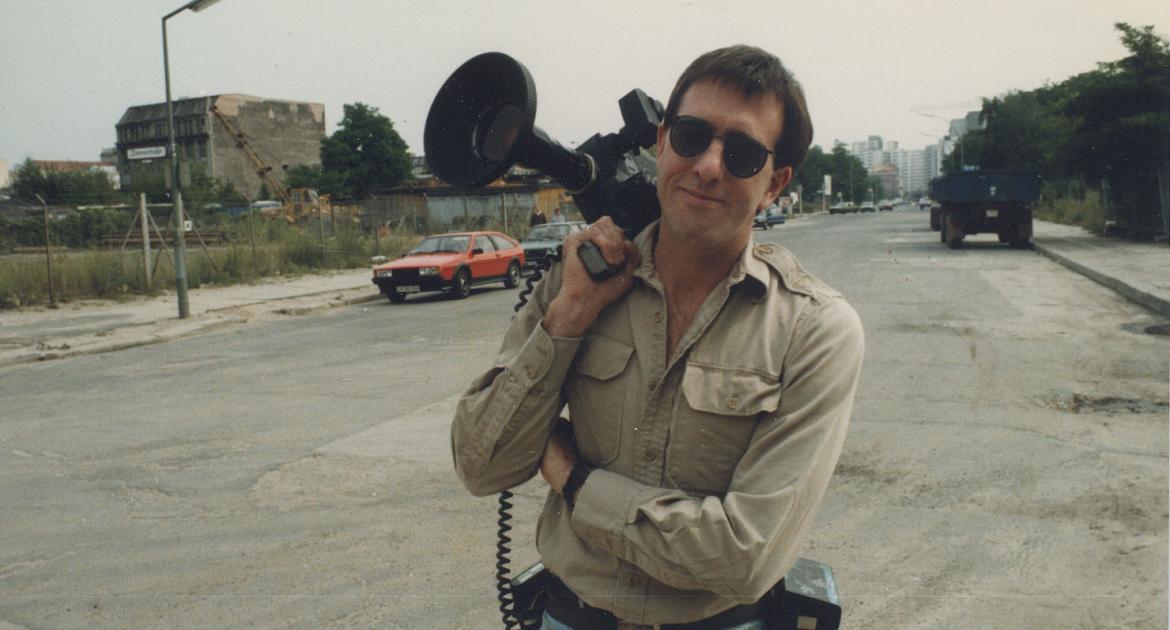

Ross McElwee Retrospective

THE EMBLEMATIC QUOTIDIAN

To create a character out of yourself in order to learn how to (re)know yourself; to look at and see yourself in others and the world in that reflection of distorted truthfulness that gives us art and its artifices. This might be one of the many ways to define the film work of Ross McElwee, who has managed to subvert and amplify certain forms in documentary expression to create a unique and irreplaceable voice in contemporary film.

Since the beginning of his career - after his stint of writing and photography had faded away - he has turned his camera to people, to film them with an intimacy that provides him knowledge about, and personal contact with, them: his friend Charleen, his father, his brother, and the workers who faithfully serving his family since childhood - all a close part of his daily life or his circle of friends - embody an important space where McElwee will make his early forays into cinéma vérité, so dominant at that time, and simultaneously the source of his film education under the auspices of one of the great figures in American filmmaking, Richard Leacock, professor at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

Both Charleen (1977), a film about his former high school teacher and friend, a major artistic and personal influence in his life with whom he would start sharing milestones, major events and nearly all of his film work; as well as Backyard (1984), when self-referential filmmaking caught on for good to become his hallmark, these are both seminal works in his career, precise exploratory probes that will inevitably lead him to his first film with complex writing and a voice split between the ensemble and the first person.

We are talking here about Sherman's March (1986), a film that would become the definitive "launch pad" for his career. Having won the Grand Jury Prize at the Sundance Film Festival and a US theatrical release, he took a definitive step forward in a register and voice that has remained nearly constant in all his films to date. In this cheerful and profound road movie, McElwee follows the devastation General Sherman left in his wake in the American South at the end of the Civil War. From the very beginning (with a map of the south and Leacock's historicist voice, which immediately mutates into the filmmaker's characteristic self-doubting autobiography), the intentions of the film are made clear: McElwee's personal, intimate story, his incessant search for unrequited love, gets interwoven together with the violent history of a country at war with itself, both because of its unresolved past, as well as because of its present - affected more by political and racial contradictions than latent ones.

This is the point when the kinetic drive that Josep María Catalá once called the body-camera gets activated, this symbiosis between human and machine that gives McElwee the chance to face his characters using a practice that is both alive and distant. The camera is ever-present, like a great eye capturing everything, creating a separation from the other, shielding him emotionally; but it is through a candid, familiar voice and a physicality let's call technological, that makes it so what is filmed opens up into confession and sincerity. Thus, after a long, funny and also painful emotional journey on which McElwee unsuccessfully seeks true love, he communicates his frustration to us in an ironically climactic ending that stokes new romantic expectations.

After an atypical venture into politics in his career, when he co-directed with Marilyn Levine Something to Do with the Wall (1991), McElwee returned to his unmistakable style with that sad but hopeful observation of death and the family, Time Indefinite (1993). Here as well, he categorically takes on one of his most recognizable attributes: restoring and bringing back to life footage from previous films, confronting it through a new verb tense, the past (his early home footage) seen from the present (the editing of the film) which is, in turn, an analysis of something that happened at a time in between the two (the events he deals with in this film in particular). This rather convoluted explanation of his dramaturgy serves to show the amazing ease with which McElwee turns the complex into something simple, something that might lead one think one could achieve the same with one's own life and a camera, thus proof of the brilliance that he packs into each of his films; islands of ongoing communication and meaning within the totality and shifting of his film work.

It is this magical harmony in time periods and narratives that explains why it is so recommendable - and enjoyable - to see McElwee's work as a whole, letting ourselves be guided by the philosophical and emotional twists and turns that he traps us in the instant we step into his experiential and creative universe. At times, it resembles formulas from series in ancient literature or modern television, such as in Six O'Clock News (1996), which starts with the same shot as in the final minutes of Time Indefinite: the face of his newborn son Adrian looking curiously at the camera and in anticipation of the acute paternal instinct to protect that he is producing in the director. A double viewpoint that gets repeated again here: one of McElwee himself, portrayed through the eyes of his son, and one of the dangerous outside world through the six o'clock news. Here we see chance, fate, a lack of control and the responsibility of bringing a child to this deranged world, one capable of destroying everything we love in one tragic moment.

Wearing everyday life as badge of honor, his filmmaking is tied to the immediate – even though he always transforms it to lend it a temporality of its own, the ordinary – even though he also observes it through extraordinary events -, and the intimate – even though he analyzes and decomposes it through images from narrative Hollywood fiction-, as in Bright Leaves (2003), where he breaks down a lesser-known work by Michael Curtiz, Bright Leaf (1950), to convert it into a genealogical search for his family roots in the state of North Carolina; an unsuccessful and consciously pathetic search, like all his searches, though transcendent enough in his analysis of a self-destructive society and the act of filmmaking itself, establishing a hidden and mysterious relationship in an apparent dichotomy between documentary and fiction.

His last film to date, Photographic Memory (2012), has one peculiarity and an anomaly, though I'd rather the reader (future viewer) be the one to decide which bag to put each one: on the one hand, it is the first time McElwee shot a film in digital format, something that forced him to consider this issue of film quality versus the immateriality of algorithms in a direct and metaphorical way; and on the other hand, it is also the first time he is involved in making a fiction film, in helping his son Adrian get on paper a screenplay that he woke up with in his head on one morning of frustrated fishing, a metaphor too and a beautiful one at that, for the complexity of parent-child relationships that have been occurring throughout the history of humankind. This first-person reflection on the bewildering passage of time and the timelessness of parental conflicts, marks a before and after in the career of a filmmaker, who willingly shapes his life to the whimsical need for artistic expression, or perhaps vice versa.

Ross McElwee's film work is solidly built upon a place that is constantly mutating between self-referential essay, confessional diary and home movies. In a highly personal and very enjoyable body of work, it combines the unstable objectivity of the documentary with the stamp of biographical subjectivity. Together with him, we enter into the emotional psyche of a philosopher of experience, the creator of a universe in which reflecting on the (id)entity of images, transmuting intimacy in art, or analytical mordacity take on new value: that of the exceptionality of a filmmaker who alters and reconfigures his personality while also creating film work that resonates universally.

Epilogue

Note how important it is to McElwee to work on the fly, the immediacy and the subsequent confrontation of one reality -his-, documented over years of audiovisual footage. It just so happens, or is going to happen, that during this DocumentaMadrid 2018, Ross McElwee himself will give a Master Class on the preparation of what will become his next film, Sherman's Redux, a documentary on the hardships he has had endure with different Hollywood producers to get his already classic documentary Sherman's March made into a fictional comedy. It also just so happens that McElwee is eager to be getting suggestions from the audience to "find my way out of this morass", to use the filmmaker’s words. And it just so happens, lastly, that you are all invited to attend if you register in advance using this link.

David Varela

DocumentaMadrid

DocumentaMadrid