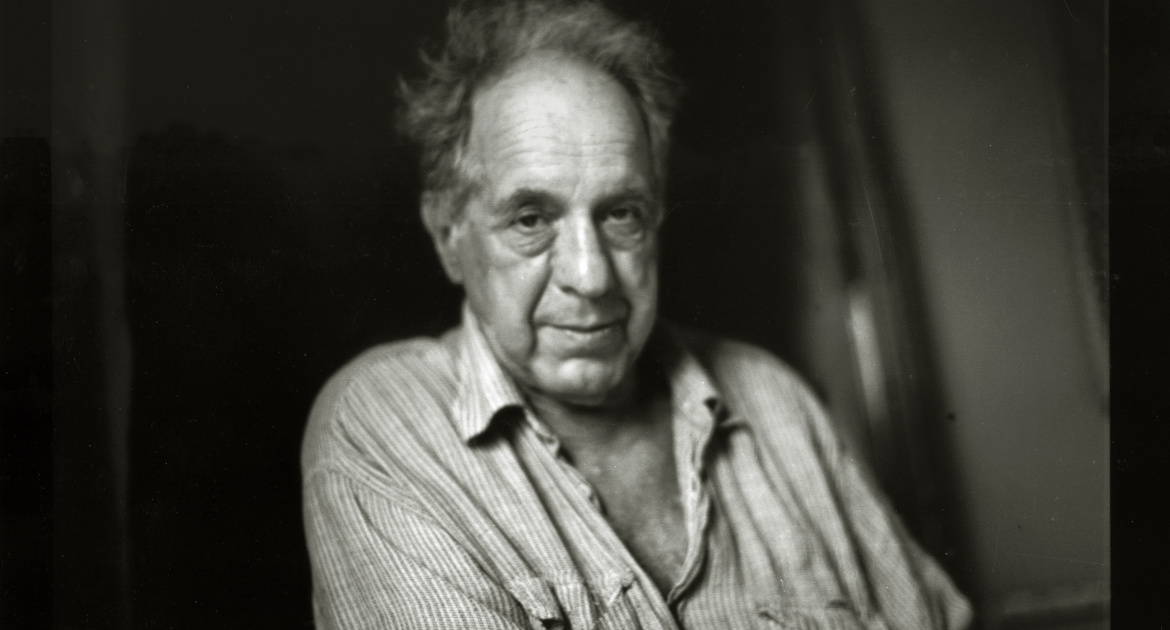

Robert Frank. Beat, Beat & Me. A complete retrospective

Photo credit: ©Dodo Jin Ming

A decision: I put my Leica in the cupboard. Enough of lying in wait, pursuing, sometimes catching the essence of the black and white, the knowledge of where God is. I make films. Now I speak to the people who move in my viewfinder. Not simple and not especially successful.

Robert Frank on his shift from photography to film

Robert Frank (b. 1924, Zurich) is one of the most well-known and acclaimed photographers in the world. Yet he was also a filmmaker, a fact that comparatively few remember or are even aware of. From 1959 onwards, he put his work as a photographer on hold to focus on cinema, going on to complete more than 25 films over a 50-year career until his death in September 2019. Many of these are regarded as seminal works within the international independent and documentary scene.

So often overshadowed by his photographic work, Frank’s films and videos have increasingly gained an international reputation; New York Times film critic Manohla Dargis called Frank “one of the most important and influential American independent filmmakers of the last half-century.” After Frank’s global breakthrough as a photographer in the 1950s with his book The Americans, his first contact with filmmaking came in 1959, when he co-directed the experimental short Pull My Daisy with Alfred Leslie. This now-classic work features narration by Jack Kerouac and a cast including Beat poet Allen Ginsberg, Peter Orlovsky, and Gregory Corso. Frank and Leslie’s film was heralded immediately as something fresh and exciting that, with Jonas Mekas writing in his “Movie Journal” column in the Village Voice that the film points “toward new directions, new ways out of the frozen officialdom and mid-century senility of our arts, toward new themes, a new sensibility.”

Frank’s film work continued this same innovative quality over the course of the next five decades and has continually defied any type of easy categorization, moving between fiction, documentary and essay film at a time when such disdain for boundaries was hardly the norm. One of its consistent features is a probing self-reflexivity, carried over from the Beat writers who provided early inspiration for both his photographs and films. Other (counter-) cultural phenomena in the US equally piqued his interest, whether protests against overpopulation (Life-Raft Earth), the search for clean energy (Energy and How to Get It), Rolling Stones concerts (his infamous unreleased Cocksucker Blues remains hard to see to this day) or the legacy of the Beat movement as it was still being forged (This Song for Jack, Harry Smith at the Breslin Hotel 1984). At a time America is once again riven by protest, viewing these urgent time capsules of past tensions and agitations could hardly be more prescient today.

The other key thread running through his oeuvre is autobiography, as Frank turned his lens on himself and his family again and again, with the results variously taking the form of more conventional self-portraiture (Conversations in Vermont, Life Dances On, Home Improvements, The Present, Flamingo, True Story) or playful experiments with re-enactment (About Me: A Musical, C’est vrai, I Remember). Given that his life was so often reflected in his cinema, it’s no surprise that his own wanderings also find their way into his work, as Frank’s films frequently left behind his US home to probe Nova Scotia (Keep Busy), Paris and Taipei (Sanyu), Germany’s Ruhr region (Hunter) and his native country of Switzerland (Tunnel, Fernando).

Aside from such thematic concerns, Stefan Grissemann’s introduction to the seminal “Frank Films: The Film and Video Work of Robert Frank”, the collection he edited with Brigitta Burger-Utzerv back in 2003 when the critical reappraisal of Frank’s work was just beginning, provides a wonderfully lyrical description of the filmmaker’s more fundamental interests: “If there were a term that could aesthetically outline Frank's work, it would be “fleetingness.” Frank's documentary pieces, but also his fictional works, possess an unbridled love of the present, a devotion to the transience of the moment. Frank is a master of radical understatement, of refusal. His style, his language and his time is the present—as though he wanted to cross the constitution of his medium that keeps time alive, having it eternally reproducible as memory. Frank's films and videos contain—at least seemingly—hardly any “great” pictures and no “distinguished” moments. His films refuse “cinema.” Anyway, Frank is not interested in being at the height of any type of “art.” These films aim to be present for the moment only in two respects—the moment that they replicate, just as much as the moment that they are observed—to then immediately “retreat” from consciousness, as if they had never been there, like dreams that you can't really piece together when you wake up. These films are not made for leaving behind tracks, they remain pale, ungraspable, are more “atmospheric” than “pictorial.” (If one looks a bit deeper, however, this impression changes: when reviewing stills from Frank's films, for example, a unique compositional beauty is immediately noticeable, a visual precision that is difficult to recognize in the films themselves. A constant fascination with this work lies in that it seems to play down, to even deny its own beauty to such an extent.)”

This complete retrospective organized by Documenta Madrid in collaboration with Filmoteca Española and Cineteca Madrid presents the entire film and video work of Robert Frank in Spain for the first time and functions as a means of celebrating Frank’s myriad achievements a year after his death at 94. It is a unique opportunity for Madrid audiences to discover the more unknown corners of his oeuvre and grapple with the American-Swiss artist’s transnational, boundary-subverting approach, which remains as vital today as it was during his lengthy, celebrated career.

Cecilia Barrionuevo, James Lattimer and Gonzalo de Pedro.

[1] Stefan Grissemann, Vérité Vaudeville. A Passage through Robert Frank’s Audiovisual Work. In: “Frank Films: The Film and Video Work of Robert Frank”, Brigitta Burger-Utzer & Stefan Grissemann (eds.), (Göttingen: Steidl, 2009), pp. 19-51, p. 20.

DocumentaMadrid

DocumentaMadrid